-

California Native Plants Unattractive to Bees

I saw this question of plants that don’t attract bees come up in an online forum recently. While this isn’t something I’ve considered before, I can see the reason, and maybe need, to install plants that might be less attractive to bees in the home garden.

It’s important to note that most California native plants play a crucial role in supporting pollinators, including bees, some plants are less likely to attract bees than others. However, it’s essential to understand that excluding bees entirely from your garden may not be ecologically sound, as they are crucial for pollination and the overall health of ecosystems. That said, if you’re looking for California native plants that are less attractive to bees, consider the following options:

California Buckwheat (Eriogonum species)

Many species of California Buckwheat have small, inconspicuous flowers that are less attractive to bees.California Fuchsia (Epilobium canum)

This plant has tubular flowers and is known to attract hummingbirds more than bees.Coyote Brush (Baccharis pilularis)

This shrub produces inconspicuous flowers and may attract fewer bees.Toyon (Heteromeles arbutifolia)

Toyon has clusters of small, white flowers that may be less appealing to bees.Lizard Tail (Eriophyllum staechadifolium)

This plant has yellow flowers and may attract fewer bees compared to other flowering plants.Coffeeberry (Frangula californica)

Coffeeberry has small, greenish flowers that are not as attractive to bees.California Lilac (Ceanothus species)

While some varieties of California Lilac are known to attract bees, others have less conspicuous flowers.California Sagebrush (Artemisia californica)

This aromatic shrub has gray-green foliage and small, inconspicuous flowers that may not attract many bees.California Sage (Salvia species)

Some species of Salvia have flowers that are less attractive to bees. Examples include Cleveland Sage (Salvia clevelandii) and White Sage (Salvia apiana).Mulefat (Baccharis salicifolia)

Similar to Coyote Brush, Mulefat is another Baccharis species with less conspicuous flowers.Deergrass (Muhlenbergia rigens)

Deergrass is a clumping grass with feathery flower heads that may be less attractive to bees.The trend I’m seeing in these are plants with small clusters of flowers. Bees may still try and get to these plants, it’s likely that the small flowers just aren’t built to give them the access they need.

For contrast, some plants like the Desert Museum Palos Verde in full bloom with it’s bright yellow flowers is a bee magnet and will be FULL of native and honey bees when in bloom.

Read: Starting a Native Plant Garden in Southern California Hardiness Zone 10

Remember that even plants that are less attractive to bees can still provide valuable resources for other pollinators, such as butterflies and hummingbirds. If possible, it’s best to create a diverse and ecologically balanced garden that supports a variety of wildlife. Additionally, the overall health of your garden and the surrounding environment can benefit from the presence of pollinators, including bees.

Why exclude bees?

While bees play a crucial role in pollination and contribute to the health of ecosystems, there are some reasons why someone might be hesitant to have bees in their garden.

Read: Native Plant Nurseries Around the San Fernando Valley

It’s important to note that bees are generally beneficial for gardens and the environment, but here are a few reasons someone might prefer to minimize bee presence:

- Allergies: Some individuals are allergic to bee stings, and the presence of bees in the garden could pose a risk to their health. In such cases, individuals may want to minimize the risk of encountering bees.

- Fear of Bee Stings: Even for those without allergies, there might be a fear of getting stung by bees. This fear could be due to past negative experiences or a general aversion to stinging insects.

- Outdoor Activities: If a garden is frequently used for outdoor activities, such as children playing or family gatherings, the presence of bees might be seen as a potential nuisance or safety concern.

- Concerns for Pets: Some people worry about the safety of their pets, particularly if they have dogs that might be prone to chasing or disturbing bees.

- Garden Aesthetics: Some homeowners or gardeners may have a specific aesthetic vision for their garden and prefer plants that are not heavily visited by bees. However, it’s essential to recognize that many pollinators, including bees, contribute to the overall health and diversity of a garden.

If someone has concerns about bees in their garden, it’s advisable to consider ways to coexist with these important pollinators rather than trying to exclude them entirely.

Creating a bee-friendly garden with a variety of plants, including those that attract fewer bees, can strike a balance between supporting pollinators and addressing specific concerns. Additionally, bee-friendly practices can help educate individuals about the importance of bees and their role in sustaining ecosystems.

Read: The Hori Hori Garden Knife: A Versatile Tool Rooted in History

-

Native Plant Nurseries Around the San Fernando Valley

Native plant nurseries are a rarity in Los Angeles. With a few notable locations like Theodore Payne, Plant Materials, and Artemisia Nursery, access to native plants and the knowledge of installing and caring for them can be challenging. Worse, if you want to buy native plants, outside of these few and far between native plant nurseries, most of the local nurseries have a limited stock of native to California plants.

most of the big box stores like Home Depot and Lowes don’t have any. Your local garden centers like Green Thumb or Armstrongs may have a few.

So why shop at a native plant nursery? A few reasons exist to buy from a nursery that strictly deals in native plants. Let’s look at each of these different reasons and put some into context.

Read: Greening Your Space: 10 Reasons to Choose California Native Plants

Preserving Native Ecosystems

One of the most critical roles of local native plant nurseries is the preservation of native ecosystems. Los Angeles County boasts a rich diversity of plant species, many of which are unique to the region. However, rampant urban development and invasive species threaten the very existence of these ecosystems. Native plant nurseries are instrumental in cultivating and propagating indigenous plants, ensuring their survival in the face of these challenges. Most source locally and grow from seed plants growing on the edges of the San Fernando Valley in the Santa Monica Mountains and Santa Susanna Mountains. Bonus: if you’re into hiking, you can see many of these native plants in the ecosystems where they naturally occur. In particular in Placerita Canyon, the Las Virgenes Open Space and the Santa Monica Mountains.

Restoring Urban Green Spaces

As Los Angeles expands, urban green spaces have become increasingly important. Local native plant nurseries provide the city with a sustainable source of native vegetation for parkland restoration projects, creating urban oases that benefit both the environment and the community. These green spaces offer a respite from the concrete jungle and provide essential habitat for local wildlife.

Read: Starting a Native Plant Garden in Southern California Hardiness Zone 10

This is an essential aspect of native plant nurseries and something I wish Los Angeles City and its various council districts would think more about. It’s a tremendous missed opportunity to not use native plants in green belts, medians, and other unused civic dirt patches often left to grow weeds or, worse, invasive, non-native plants.

Water-Wise Landscaping

In a region plagued by droughts and water scarcity, landscaping choices significantly impact water conservation. Native plants, adapted to the local climate, require less water than non-native species. By promoting native plants, local native plant nurseries help homeowners and businesses create attractive, water-efficient landscapes that reduce the strain on local water resources.

The city and water districts are doing better with lawn replacement rebates, composting seminars, and tree giveaways. Frequently, the LADWP gives trees away to re-green the city. Sadly, the trees they give away are often not native and not beneficial to the bugs and birds of the San Fernando Valley.

Visit the California Botanic Garden

Another harmful alternative to lawns is AstroTurf lawn replacements and xeriscape rock gardens. While they can be done well, most of the rebate programs initiated over the last few years have resulted in hideous yards filled with oddly shaped non-native cacti and succulents or soil biology-killing turf with weeds growing at the edges.

Biodiversity and Wildlife Habitat

I can’t stress this enough: native plants are the backbone of healthy ecosystems, providing food and shelter for various wildlife, including birds, insects, and mammals. By cultivating and selling native plants, local nurseries indirectly contribute to restoring wildlife habitats in urban and suburban areas. This, in turn, leads to increased biodiversity and the revival of local animal populations.

Read: Watering Newly Planted California Native Plants

Green lawns, while pleasant to look at, are huge ecological dead zones and do little to support native wildlife. A thirsty crop, green grass lawns account for a tremendous use of water. One 10×10 square foot of yard can consume 62 gallons of water. Your consumption may vary, but it’s expensive and wasteful for a crop of grass that exists so the dog has a place to poop or the kids to occasionally play.

Read: Drought Tolerant vs. Native Plants

Instead, imagine investing in a habitat that’s good for the bugs and birds and feeds nature rather than taking from it? By replacing your green lawn with native plants from a local native plant nursery, you can put it back into a system that has been missing for generations.

Educational Opportunities

Local native plant nurseries serve as valuable educational resources. They offer workshops, plant sales, and tours that engage the community and promote environmental awareness. These nurseries empower Angelenos with the knowledge and tools to make informed landscaping, conservation, and sustainable living choices.

Read: California Native Plants Unattractive to Bees

Theodore Payne is a standout for educational classes. Their offering of classes supports several native plants enthusiast needs. Right Plant, Right Place is a great class to learn how to think about planting natives. If you’re a commercial gardener, they offer certification classes on installing and caring for native plants. And, if your interests are in growing natives, you can learn how to grow them from seed. The SAMO Fund in Thousand Oaks has tremendous educational offerings without the commercial nursery.

Community Building

Beyond their environmental impact, local native plant nurseries foster a sense of community. They bring together like-minded individuals with a passion for native plants and conservation. Community involvement in these nurseries creates a network of advocates for local biodiversity and strengthens the bonds between residents and their natural surroundings.

This is highlighted in adjacent plant activities like volunteering, classes, and communities around native plants. These groups exist beyond the native plant nursery in community organizations like the California Native Plant Society, Sierra Club, and others whose focus is on the environment and frequently host gatherings, lectures, plant sales, and volunteering events. One such event is a monthly weeding and restoration meet-up in the Sepulveda Basin Wildlife Reserve.

Read: CA Native Plants in Bloom in March

The importance of local native plant nurseries in Los Angeles cannot be overstated. These hidden havens of biodiversity preservation, restoration, and education play a crucial role in safeguarding the region’s native ecosystems, promoting water-wise landscaping, and building a stronger community. Through their dedication to cultivating native plants, these nurseries contribute to a greener, more sustainable San Fernando Valley, where nature and urban life coexist harmoniously.

Native Plant Nurseries around the San Fernando Valley

Theodore Payne Nursery

10459 Tuxford Street, Sun Valley, California 91352

Altadena

3081 Lincoln Ave, Altadena, CA 91001, USAGlassell Park

3350 Eagle Rock Blvd, Los Angeles, CA 90065, USASilver Lake

3024 La Paz Dr, Los Angeles, CA 90039, USA

Matilija Nursery

8225 Waters Rd, Moorpark, CA 93021Artemisia Nursery

5068 Valley Blvd, Los Angeles, CA 90032Hahamongna Native Plant Nursery

4550 Oak Grove Dr, Pasadena, CA 91103CNPS LA/SMM

annual plant saleDevil Mountain Wholesale Nursery

3200 W. Telegraph Road

Fillmore, CA 93015 -

Desalination in Southern California: Balancing Water Supply, Ecosystem, and Economy

Southern California, with its arid climate and ever-growing population, faces constant challenges in ensuring a stable and sustainable water supply. One solution that has gained considerable attention in recent years is desalination. This process involves the removal of salt and other impurities from seawater, making it a potentially valuable source of freshwater. In this blog post, we will explore the practicality of desalination water plants in Southern California and examine their effects on the ecosystem and economy.

Desalination in Southern California

Addressing Water Scarcity

Southern California has long grappled with water scarcity issues, exacerbated by droughts and population growth. Desalination offers a promising alternative to traditional freshwater sources, providing a reliable and drought-resistant supply of clean water.

Read: Drought Tolerant vs. Native Plants

Technological Advancements

Advancements in desalination technology have made the process more efficient and cost-effective, making it a viable option for water supply augmentation in the region. Facilities like the Carlsbad Desalination Plant have proven the feasibility of large-scale desalination operations.

Ecosystem Impacts

Marine Life Concerns

One of the primary concerns surrounding desalination plants is their impact on marine ecosystems. Seawater intake and brine discharge can harm local marine life. However, modern desalination facilities employ advanced intake and discharge systems to minimize these effects, often exceeding regulatory standards.

From the NY Times: Arizona’s Pipe Dream.

Salinity Disruption

Discharging brine back into the ocean can disrupt local salinity levels. This can harm marine species adapted to specific salinity ranges. Research and monitoring are crucial to understanding and mitigating these impacts.

Read: Southern California Planting Zones

Economic Considerations

Initial Investment vs. Long-Term Benefits

Desalination plants require substantial upfront investment, making them more expensive than other water supply options. However, over the long term, they can prove cost-effective, especially in drought-prone regions.

Job Creation and Economic Growth

Desalination plants can stimulate local economies by creating jobs and generating revenue. Additionally, a stable water supply can attract new businesses and support existing industries, ultimately contributing to economic growth.

Reducing Dependency on Imported Water

Southern California currently imports a significant portion of its water supply from distant sources. By investing in desalination, the region can reduce its reliance on imported water, potentially saving costs in the long run.

Read: Conserving Water in Southern California

Desalination plants in Southern California offer a practical solution to water scarcity issues. While they present challenges to the ecosystem, modern technology and responsible management can mitigate these concerns. Furthermore, the economic benefits, including job creation and reduced dependency on imported water, make desalination a valuable investment for the region. Striking a balance between water supply, ecosystem preservation, and economic growth is crucial as Southern California continues to seek sustainable water solutions for its future.

-

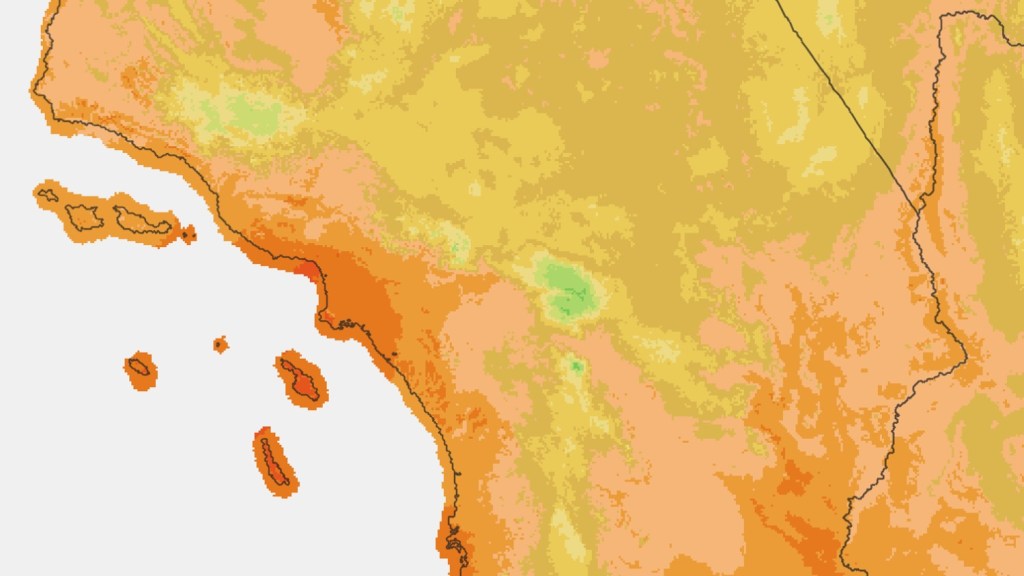

Southern California Planting Zones

Southern California’s diverse climate and topography create a unique tapestry of planting zones, each with its own set of environmental conditions and challenges. From the coastal regions with salt spray to the hot arid inland valleys and the cool, and sometimes damp, mountain ranges, the variety of microclimates results in distinct planting zones that gardeners and horticulturists must consider when selecting and cultivating plants. Given the level of interest, especially as it relates to planting California native plants, I would like to delve into the reasons behind the existence of different planting zones in Southern California and explore the unique characteristics that make each zone special.

Why Different Planting Zones?

Southern California’s complex geography and climate variability contribute to the existence of different planting zones. Factors such as elevation, proximity to the coast, prevailing winds, and temperature variations all play a crucial role in defining these zones. The Pacific Ocean’s cooling influence, the coastal mountains, and the presence of desert areas all contribute to a wide range of microclimates across the region.

Read: Drought Tolerant vs. Native Plants

Understanding the USDA Hardiness Zones

The USDA Plant Hardiness Zone Map is a valuable tool that categorizes different areas based on their average annual minimum temperatures. In Southern California, the zones range from 5b to 11a. The higher the zone number, the warmer the climate, and the broader the range of plants that can thrive.

Exploring the Unique Planting Zones

Coastal Zones (Zones 10a-11a)

The coastal regions, with their mild and temperate climate, are the most sought-after areas for gardening. Zones 10a and 10b are characterized by their frost-free winters and cool summers. These zones are suitable for a wide variety of plants, from tropical species to Mediterranean flora. The moderating effect of the Pacific Ocean ensures that extreme temperatures are rare.

Read: Embracing the Fifth Season

Calling it a coastal zone may seem like a misnomer with the inland valleys seeming far from the marine influence of the Pacific. Yet it is exactly that influence that moderates the valleys and keeps them from becoming hot dry deserts.

Coastal zones include Thousand Oaks, Oxnard, Los Angeles, Simi Valley, Sherman Oaks, Lakewood, Santa Ana, Huntington Beach, San Clemente, and San Diego.

Read: The Impact of Climate Change on Planting Zones: A Look Ahead to 2050

Plants that do well in Coastal Zones 10a, 10b, and 11a:

- Blue-eyed Grass – Sisyrinchium bellumBush Sunflower – Encelia californica

- California Buckwheat – Eriogonum fasciculatum

- California Fuchsia – Epilobium canum

- Coast Live Oak – Quercus agrifolia

- Hummingbird Sage – Salvia spathacea

- Lemonade Berry – Rhus integrifolia

- Spiny Redberry – Rhamnus crocea

- Toyon – Heteromeles arbutifolia

- Western Sycamore – Platanus racemose

- White Sage – Salvia apiana

Read: Starting a Native Plant Garden in Southern California Hardiness Zone 10

Inland Valleys (Zones 9a-9b)

Moving slightly inland, the valleys experience warmer summers and cooler winters compared to the coastal regions. Zones 9a and 9b encompass cities like Los Angeles and San Diego. Gardeners in these zones need to select plants that can handle occasional frost and warmer summer temperatures.

Inland valleys include Riverside, San Bernardino, Redlands, and Santa Clarita.

Plants that grow well in Zones 9a-9b:

- Coulter’s Matilija Poppy – Romneya coulteri

- Big Saltbush – Atriplex lentiformis

- Bladderpod – Peritoma arborea

- Hollyleaf Redberry – Rhamnus ilicifolia

- Chaparral Yucca – Hesperoyucca whipplei

- Mulefat – Baccharis salicifolia

- California Sagebrush – Artemisia californica

- Purple Needlegrass – Stipa pulchra

- Common Yarrow – Achillea millefolium

- Coast Prickly Pear – Opuntia littoralis

- California Primrose – Oenothera californica

- Quailbush – Atriplex lentiformis ssp. Breweri

- Laurel Sumac – Malosma laurina

- As well as the list of plants in Zone 10.

Foothills and Mountain Zones (Zones 8a-8b)

As you ascend into the foothills and mountainous regions, the climate becomes more challenging. Zones 8a and 8b are characterized by colder winters, snowfall, and shorter growing seasons. While these zones present unique planting opportunities, gardeners need to choose hardy plants that can withstand cooler temperatures and shorter growing periods.

Read: The Hori Hori Garden Knife: A Versatile Tool Rooted in History

Zone 8a and 8b in Southern California include Lancaster, Victorville, Banning, Death Valley, Tehachapi, and Hemet.

Plants that grow well in Zone 8 in California include:

- Deergrass – Muhlenbergia rigens

- Fremont Cottonwood – Populus ferment

- Desert Willow – Chilopsis linearis

- Desert Globemallow – Sphaeralcea ambigua

- Interior California Buckwheat – Eriogonum fasciculatum var. polifolium

- Red Willow – Salix laevigata

- Hollyleaf Cherry – Prunus ilicifolia

- Desert Wild Grape – Vitis girdiana

- Antelope Bitterbrush – Purshia tridentata

- Tomcat Clover – Trifolium willdenovii

- Black Oak – Quercus kelloggii

- Scrub Oak – Quercus berberidifolia

- Red Osier Dogwood – Cornus sericea

- Incense Cedar – Calocedrus decurrens

- Jeffrey Pine – Pinus jeffreyi

- Black Cottonwood – Populus trichocarpa

Note, many may be regionally specific to your location, facing, and precipitation profile.

Desert Zones (Zones 5b-7b)

In the southeastern part of Southern California lies the desert region, with zones 5b to 7b. This area experiences hot, arid summers and chilly winters. Succulents, cacti, and other drought-tolerant plants are best suited to thrive in these zones, where water conservation is of great importance.

Areas of Southern California that include zones 5b-7b include Big Bear Lake, Alpine Village, Part of Inyo County, Fresno County, Bear Valley, Big Bear, Riverside County, San Bernardino County, and small parts of Los Angeles County. While this is a broad list, many areas are likely microclimates, peaks, or small areas in rain shadows and do not get large volumes of rain.

- coffeeberry – Frangula californica

- Sierra Redwood – Sequoiadendron giganteum

- California Goldenrod – Solidago velutina ssp. californica

- Giant Chain Fern – Woodwardia fimbriata

- Quaking Aspen – Populus tremuloides

- False Solomon Seal – Maianthemum stellatum

- Lodgepole Pine – Pinus contorta

- Balsam Fir – Abies concolor

- Interior Live Oak – Quercus wislizeni

- Ponderosa Pine – Pinus ponderosa

- Irisleaf Rush – Juncus xiphioides

Interestingly, many of the planting zones share species between them. California native plants, while diverse and widespread are amazingly hardy and resilient throughout, especially in native plant gardens with supplemental watering and care.

Read: Why I Garden

A great resource to consult is the website Calscape which has a handy tool to find the plants that grow specifically in your region.

Southern California’s diverse planting zones provide an incredible array of gardening opportunities, each with its challenges and rewards. Understanding the unique characteristics of each zone allows gardeners and horticulturists to select the right plants for their specific microclimate, ensuring a successful and vibrant garden. Whether you’re cultivating coastal blooms, valley greens, mountain treasures, or desert jewels, embracing the diversity of Southern California’s planting zones can lead to stunning landscapes that mirror the region’s rich ecological tapestry.

-

Embracing the Fifth Season

Navigating California’s Transition from Summer to Fall

In the golden state of California, where buckwheat turns from cream to rust against the backdrop of deep blue skies and dry Santa Ana winds, there exists a unique phenomenon known as the “Fifth Season.” This transitional period, which falls between the end of summer and the onset of fall, carries a distinct character that sets it apart from the traditional four seasons. Often referred to as the “fire season” due to its association with wildfires and preceding the elusive late fall rains, the Fifth Season holds both challenges and beauty, shaping the lives and landscapes of those who call the SoCal Mediterranean climate home.

The Mediterranean Climate: A Precursor to the Fifth Season

California’s Mediterranean climate, characterized by warm, dry summers and mild, wet winters, sets the stage for the Fifth Season. The region’s reliance on distinct wet and dry periods makes this transitional time essential for ecological balance and water availability.

Unlike other areas of the world, the climate in SoCal turns on a wet winter into spring and then a very dry (usually) summer into late winter. That’s not to say there isn’t some rain, Typically, summer into fall is dry, hot, and still before the winds come with the start of autumn.

Rea: Drought Tolerant vs. Native Plants

The Fifth Seasons Arrival: Embracing Change

This transitional period often begins in late August and extends into September, introducing Californians to a sense of anticipation and change. When it starts, the stillness and almost oppressive heat are like a cloak that smothers the breath and makes the air feel like a tight embrace. As summer’s heat gradually wanes, the Fifth Season emerges with a unique blend of characteristics. Towards the end, the air becomes crisper, and the sun’s intensity softens, offering respite from the scorching days of summer.

Read: Conserving Water in Southern California

Fire Season and Environmental Concerns

The term “fire season” is not without reason. As the Fifth Season progresses, the landscape becomes increasingly dry, creating favorable conditions for wildfires to ignite and burn the hillsides. This annual challenge poses a significant threat to both human communities and natural ecosystems. As a result, residents and authorities must be vigilant, implementing preventative measures and preparedness strategies to minimize the risk. And, as one can imagine, with climate change, fire season is often lasting longer and causing more havoc on communities that are increasingly springing up in the wildlife interface.

Fire seems to have always played a part in our existence, at least in the last 10+ millennia. Scientists and researchers have a suspicion that our ancient ancestors shaped the landscape and wiped out the megafauna with it. Yes, fires are a part of ancient tradition and larger ecological control, but it’s been part of our human history for a while now. In the Fifth Season, fire has become a constant threat.

Read: Native Plant Nurseries Around the San Fernando Valley

The Illusive Fall Rains

One of the most intriguing aspects of the Fifth Season is its precursor to the fall rains. These early autumn rains, often erratic and unpredictable, mark the end of the fire season and usher in a time of renewal. The smell of rain on parched earth signals a shift in the atmosphere, revitalizing flora and fauna.

This year, ahead of the Fifth Season, we have been graced with a deluging Tropical Storm that is said to be dropping 2-10 inches of water on the region. While the surprise water from the storm may be a welcome reprieve from having to water outside plants, It may have some damaging unforeseen impacts on seedbanks and ecosystems unaccustomed to rain this time of year.

Read: Why I Garden

Navigating the Fifth Season: Recreation and Reflection

Despite the challenges posed by wildfires, the Fifth Season also offers unique opportunities for Californians. The cooler temperatures encourage outdoor activities like hiking and camping, while the changing landscape provides a canvas for reflection and artistic inspiration. This is especially true as it stretches into September and October. The cool crisp air and the earlier setting sun sets the mood for many as the year races to its end.

Word of caution: even with the cooler crispier evenings, the daytime temps could still climb into triple digits. Heat exhaustion and sunstroke are still possible if working too long in the garden without sun protection.

Cultivating Resilience: The Fifth Seasons Lesson

In the heart of California’s Mediterranean climate, the Fifth Season bridges the gap between summer and fall, bringing a blend of challenges and transformative beauty.

The Fifth Season is a reminder of nature’s unpredictability and the necessity of adaptability. Californians have learned to embrace the challenges and beauty of this unique period. That knowledge fosters a sense of community and collective responsibility for safeguarding their environment, at least for those paying attention to that sort of thing. While the fire season presents difficulties, the imminent fall rains bring with them a renewal of the land and plants that grow on it. Navigating this transition, Southern Californians exemplify resilience, adaptability, and a deep connection to the natural world around them. The Fifth Season with its fires and rains, leaves an indelible mark on the state’s landscape and its people, shaping their perspectives on change and the enduring cycle of life.

-

California Botanic Garden

The California Botanic Garden is an oasis of botanical diversity and conservation. Located in Claremont, California, the garden spans 86 acres of natural landscapes. As a native garden, it’s s a sanctuary for California plants, making it a vital resource for research, and preservation.

One of the garden’s defining features is how it showcases the incredible biodiversity of the state. Visitors can explore a wide range of ecosystems, from arid deserts to lush coastal regions, discovering over 2,000 different plant species. A living museum, it provides a unique opportunity to connect with California’s rich botanical heritage.

Read: Drought Tolerant vs. Native Plants

The California Botanic Garden is a beautiful place to visit and a hub for research and conservation play a crucial role in preserving endangered and rare plants through seed banking and propagation. Garden staff and scientists work with institutions worldwide to study California’s unique plant life.

One of my favorite features of the garden is the seed image database. Photographed by research associate, John Macdonald, the photos are an attempt to gather images from every taxon stored in the seed bank. As a horticulturalist, having this resource to compare and confirm what a species seed looks like is a tremendous asset.

Read: Starting a Native Plant Garden in Southern California Hardiness Zone 10

Education is another cornerstone of the garden’s mission offer a wide range of programs and workshops for visitors of all ages. These workshops show visitors the importance of addressing climate change and habitat loss.

Visitors of the botanic garden can also enjoy beautiful walking trails, themed gardens and educational exhibits. Art exhibits are also used to help provide insights into California’s botanical diversity. The serene and picturesque setting makes for an ideal place for nature enthusiasts and families seeking a tranquil escape.

The California Botanic Garden in Claremont, California, is a remarkable institution. Its dedication to the study of native California plants makes it a fantastic resource for any would-be gardener. With its stunning landscapes and conservation initiatives, the garden is a vital resource for SoCal. A visit to this botanic jewel is not only a feast for the senses but also an opportunity to appreciate the natural beauty of California’s native flora.

-

Restoring the Sepulveda Basin Wildlife Reserve

A Before and After Slice of Habitat Restoration in the Sepulveda Basin Wildlife Reserve

In September 2019, a fire roared through the Sepulveda Basin. Starting in the driest period of the year the fire burned from Victory Boulevard to the east side of the wetland lake that sits in the middle of the wildlife reserve. The fire turned what was a lush but dry habitat into a moonscape. Plants that had survived for years were reduced to ash. Soil that was covered in grass, mustard, and native plants was scoured down to exposed clay soil. Nowhere was this more obvious than in the west field that runs from Burbank northward along Woodley Ave.

This was how I rediscovered the Sepulveda Basin in late 2020.

Working remotely because of the pandemic, like many, I spent months under a lockdown that left me depressed and isolated. In that state, one mid-weekday, I decided to go to the wildlife reserve and get out into nature for a walk. To my horror, I discovered that little had come back since the fire. What had been wiped out was still just as barren as it had been a year before. My understanding of how habitats recovered from the fire was limited and seeing this proved it.

Read: Observing the Sepulveda Basin Wildlife Reserve in May

With the shock of the situation, I wanted to find a way to help fix it.

While doing some research, I stumbled upon the Sepulveda Basin Wildlife Reserve Steering Committee. There I found a group that has been meeting twice a week for the last decade to remove invasive weeds (most recently short pod mustard) from the high public traffic areas of the reserve. At the time, I had grown a dozen toyon (Heteromeles arbutifolia) from seed and wanted to find a good home for them. Seeing the opportunity, I contacted this group and offered them to plant into the space.

As luck would have it, the weekday weeding leader, George, was organizing a monthly weeding activity on weekends right at the same time. I quickly became a volunteer, planting all the toyon I had grown. I stayed and have been back to volunteer ever since.

In 2022, I decided to kick things into overdrive.

Restoring Habitat

After a few years of volunteering, weeding, and occasionally planting, I decided to try and undertake a larger project.

We had been toying with the idea of a disseminated nursery. Essentially, with the guidance and encouragement of our expert horticulturalist, Robert—himself a native plant grower and gardener, we started producing native plants at home to use in the Sepulveda Basin Wildlife Reserve.

Read: Observing the Sepulveda Basin Wildlife Reserve in July

With a home nursery of almost 200 plants, we worked to clear the weeds and spread mulch to suppress new weedy growth. I was also keen to hold as much moisture in the soil given summer sun turns the cold season loamy clay soil into adobe bricks without any canopy or ground cover.

In October 2022, we dropped 35 plants, moved mulch, and watered in a space along the west side of the creek. It was a great start to what would be a busy planting season. And then, not two weeks later, all 30 had been pulled up and vanished.

We were devastated.

Worse, whoever had pulled them out did so methodically by removing the rabbit cages pinned to the ground to protect them, setting them to the side. It did not seem malicious, and I do not believe it was theft. The area is in a very dense urban city with a large volume of unregulated day and nighttime traffic.

Refusing to be discouraged, we leaned into the setback and, in November, started planting on the north side of the lake.

New Ground

With renewed conviction, we started planting on the north side of the reserve. It was slow going at first. Many old and dry weeds that had not been burned needed to be removed, and there was little in the way of preparation. We did have a 5-yard pile of mulch that Parks and Recreation had procured for us and a blank canvas.

Unlike the last time, with this new plot, we opted to plant in weekly intervals dropping in 10-15 plants at a time, moving mulch, and watering as we went. As the cold settled in we pushed on, declaring it to be the “perfect planting season.”

In the new year, we battled illness, weeks of frost, and an onslaught of rain that kept us from planting for weeks at-a-time. The good news was that we did not have to water as much as we thought which was a huge help given how everything was hand watered from the lake.

Working nearly every weekend with help from family and friends—both old and new, we are fast approaching the 8-month mark since breaking ground. What was amazing was the space looked nothing like it did in November of 2022. The moonscape is disappearing.

With diligent weekly inputs of time, sweat, and some blood, we have restored almost a half-acre of land back to a semi-natural state. Every plant installed is regionally appropriate and put in with the changing ecosystem in mind. There are 6 new trees, more than 80 shrubs and annuals, and many islands of flowers filling the space with a vivid display of color. On top of that, the toyons planted in late 2020 and 2021 have matured and are beginning to show signs of flowering, a first for them since being planted. Older plantings are undergoing a second-year growth cycle as wild native sunflowers have resprouted and flowering.

All this positivity does not come without a degree of loss. Since we started planting, we have lost more than a dozen plants to the elements. Flooding from the rains decimated a few, but human interventions have played a part, too. As I mentioned, the space exists in a high-density urban ecosystem where accidents can happen. Many of our losses result from reckless stumbles, shortcut takers, or wild animals feverishly looking for their next meal. These things happen. With browsing prevention cages and the frequency of our human presence, the volume of issues seems to have diminished. This was especially true once we plotted footpaths through the planting areas.

Public Impacts

One of the loveliest outcomes of working to restore the space is the compliments from passers-by. Not because they represent some ego boost or congratulation. Rather each passer-by that sees the work put into the space can see California native plants reemerging through the invasive mustard. It is a tangible change to the wildlife reserve that, for the last 3 years, has been devoid of color, texture, and life. Every comment from a walker, birder, or family on an outing is a new opportunity to share the value of what a native plant garden could look like.

So far, the public loves it.

There have been a few unconvinced about the virtues of removing invasive plants. But most people get it. With the paths cut into the mulch, most visitors to the space have been aware of the work and respectful of the efforts put into it. We still have issues with brush and barriers moving, but most of the plants can hold their own making disturbances less worrisome.

What makes it worthwhile is seeing the plants in their natural setting living their natural life. Seeds that were scattered (loose and in seed balls) have come up and are producing seeds to replenish the seed bank for next year’s growth.

As we approach the one-year mark, I am excited at the possibility of what’s to come. More planting, more growth, more of the landscape returning to a natural state. Life is returning to a once lifeless place. I expect to see more insects, more birds, and more plants as the native seed bank is replenished pushing deeper into the damaged habitat. It will not happen without the human intervention and the hard work of the weekly California Native Plant Society weeders and the volunteers with Friends of the L.A. River and San Fernando Valley Audubon Society. Hopefully, it makes this work easier to do. The greatest lesson I have learned is that restoring native habitat in California is hard work and requires an army of volunteers, supporters, and boosters to help cheer them on.

It’s good work. Better when you can see a clear before and after picture to get a measure of the work.

Big thanks go out to George W., Robert K., Steve H., Ann A., Jess A., Nestor M., Nate S. and all those that have helped this project along the way.

Interested in volunteering in the basin?

-

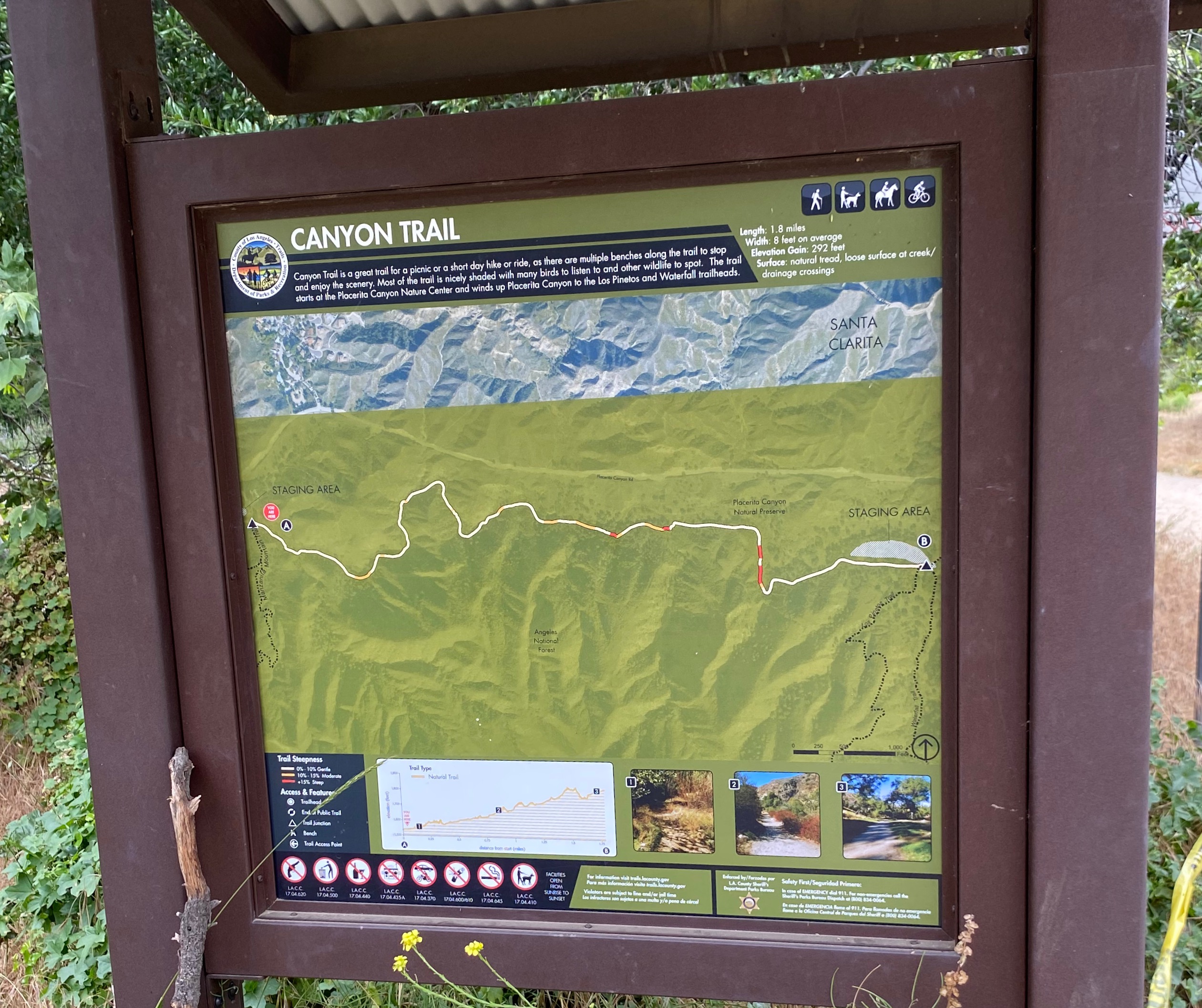

Observing Placerita Canyon

California Naturalist Outing

Placerita Canyon State Park

12:20 a.m.-3:30 p.m.- Route: From the parking lot near the nature center, across the creek to the start of trail.

- Weather: Cool and overcast entire time. 65°F

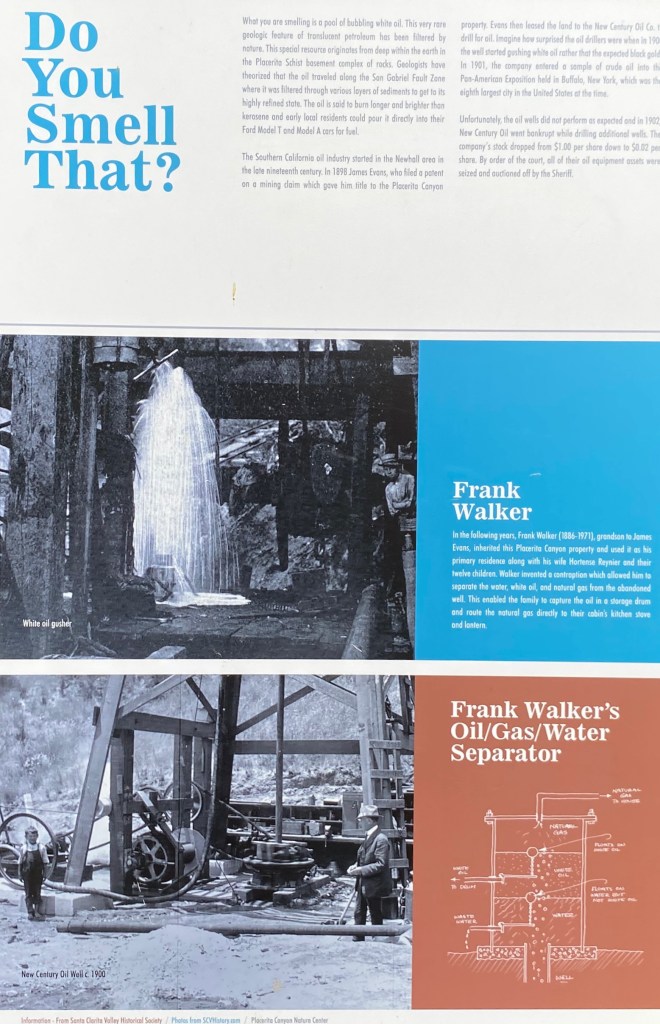

This last week I had the opportunity to observe Placerita Canyon in Newhall, California. It’s a relatively small park/open space full of native California plants and animals and a thriving ecosystem not overtaken by invasive mustard and thistle.

Located north of the San Fernando Valley, Placerita Canyon has a rich history as a potentially viable space for oil and agriculture but is unable to accomplish either. With some wide-open spaces deep, natural “white” oil seeps convinced early settlers that there was an opportunity and promise to seep from under the ground. But, like all things that seem too good to be true, the oil was not viable and only supplied the homestead.

On this day, the Placerita Canyon Open Space was full of nature enthusiasts and hikers around the nature center. On the trail, I could count the number of group hikers on one hand, with no mountain bikes on the trail. I can’t say if this was normal for a weekday for the space, but by comparison with similar spaces like the Marvin Braude and the Upper Las Virgenes Canyon, the Placerita Canyon trail was empty and very easy to navigate.

Some of that emptiness might be because of the trail’s proximity to water and the creek crossings needed to make it to the end of the Placerita Canyon trail. I was surprised to navigate almost a half dozen creek crossings following the path of the trail. In years past, my experience in Placerita Canyon was of a dry creek bed and little to no vegetation along the way. This time, Placerita was flush with a full growth of riparian plants that included: sycamores, mule fat, fuchsia, and black sage. It was also full of poison oak, which was good to see, but hard to navigate in some spots. The canyon was also home to many coast live and valley oaks. It really had the appearance of a healthy and thriving riparian plant community.

Running Creeks and Flowing Water

Also in great abundance was water. From the creek flowing down Placerita Canyon to seep water coming from under the rock faces, it was evident just how abundantly the rains had saturated the area. Along the canyon wall, you could see moisture seeping into the open creek bed. As a bonus, lanceleaf liveforever dudleya adorned the wall sending spikes of flowers into the space above the trail like fireworks with red and orange flowers. I was surprised just how many lanceleaf’s there were in Placerita, but they seemed to be a thriving colony all along the trail.

Another plant that seemed to have a dominant foothold in Placerita was the yerba santa. In spots, the tough-looking bush seemed a mono-crop of thick green leaves. Even more spectacular was that every plant was in full bloom and covered in light blue-purplish flowers. This is one of my favorite plants in the hills over SoCal. My first few encounters with it were in the Upper Arroyo Seco where it was growing sparsely along the hillside. Here, in the canyon at Placerita, it was everywhere. Almost to the point that I wondered what species or plants it was pushing out of the ecosystem. In only a few locations did I see lemonade berry, toyon, or ceanothus. But the Yerba Santa was everywhere. It really had found its happy place there.

Invasive Impacts

Another plant I didn’t see a lot of was mustard. There was some along the trail edges. In the wider open spaces, not as much as you would imagine. I wonder how much the lack of mustard correlates to the Placerita Canyon space being a healthy native ecosystem. I read recently about how productive native plant communities don’t allow invasive mustard because the introduced plant can’t get a toehold into the healthy ecosystem. It’s when that healthy ecosystem is drought or fire-stressed that mustards and invasive grasses can get in and spread.

Further back in the canyon, I did see a lot of grasses and oats that had all set and dropped seed. Mustard seemed to have a little more of a presence, but not overwhelming as with other locations geographically adjacent to Placerita Canyon.

Anthropogenic Impacts

While it was a pristine natural space, there were numerous man-made improvements.

Most significant were trail rails that seemed to exist to slow downhill traffic and function as break checks for cyclists. I say this as the post and rail fences sat as diagonals to one another across the trail, seemingly in locations that would be prone to fast downhill speeds.

Another trail feature was LA County trail markers every few hundred feet. I must admit, I liked these as they were good indicators of where to go, which way to look for an invisible trail, or just confirm I was in the right place. In some places, these trail signs told you how far you had traveled from the start (and how far to the end) at quarter-mile intervals. This was particularly nice on the way back to encourage a weary hiker. While they were a good waypoint, they stood in stark contrast to the otherwise natural setting.

The last bit of artificial/human incursion I observed was the creek crossings. As an organic thing, using rocks and fallen branches to make slippery bridges is good and there were plenty of these throughout. In one location along the Placerita Canyon trail, some clever hiker used a road crew sign horse making for a giant unnatural (and slippery) footbridge. Yes, I was glad to keep my feet dry when moving over the terrain, but disappointed to have to do it with a giant piece of plastic that spanned a third of the creek.

In the Back Canyon

Reaching the staging area in the back of the Placerita Canyon trail, I made a short run up the Waterfall Trail to observe the falls and habitats in the narrower space. Like the trail leading to it, the Waterfall trail had some early elevation gains with hand-hewn steps and slick rock faces, all surrounded by large grows of poison oak, toyon, and what looked like vining grape. There were lots of birds in the tighter canyon and below, chaparral yucca and beautiful purple grass and tree tobacco, all within a short distance from one another.

I did spot some lovely silverpuffs and soap plants in the back of the Placerita Canyon trail as well as clumps of clarkia and dodder. Maltese Thistle was there, too.

Eventually, the slick climbs from trail to trail tore my pants, so I opted to run around and head back to the start. The tear occurred in a year-old pair of Carhartt canvas pants that seemed sturdy enough for the butt to slide down the rock face. I mention this for others who climb the Waterfall trail, be warned that with water flowing, it might be most prudent to descend in some locations on your butt to avoid a nasty topple into more hard rock. I didn’t fall but felt my older Keen hikers lose some grip.

Under a still overcast June sky, I headed back down the trail dry crossing all but the last without planting a foot squarely into the water and concluded my outing at Placerita Canyon at about 3 P.M. All tabulated, I really liked this space and felt like its ease and accessibility really made for an excellent opportunity to explore and see the natural world in a lot of different contexts. There being several side trails gives me a reason to come back soon and observe more of what Placerita Canyon in Newhall has to offer.

Field Observations

- “White” oil.

- Lots of signage.

- Few hikers.

- No mountain bikers.

- Trail crossing rails.

- Stream crossing using construction materials.

- Lots of visitors around the nature center.

Observed Species

- California Sage – Artemisia californica

- Valley Oak – Quercus lobata

- Coast Live Oaks – Quercus agrifolia

- Black sage – Salvia mellifera

- Mustard (field mustard?) –

- Common wild Oat(?) – Avena fatua

- American Bird’s-foot Trefoil – Acmispon americanus

- Milk Thistle – Silybum marianum

- Maltese Star Thistle – Centaurea melitensis

- Buckwheat – Eriogonum fasciculatum

- Deerweed – Acmispon glaber

- Purple Clarkia – Clarkia purpurea

- Southern Bush Monkeyflower – Diplacus longiflorus

- Acmon Blue – Icaricia acmon

- Western Fence Lizard – Sceloporus occidentalis

- Poison Oak – Toxicodendron diversilobum

- Western Sycamore – Platanus racemose

- Wavy-leafed soap plant – Chlorogalum pomeridianum

- Silverpuffs – Uropappus Uropappus lindleyi

- Rock Phacelia – Phacelia californica

- or could be Mountain Phacelia – Phacelia imbricata ssp. imbricata

- Hairy Ceanothus – Ceanothus oliganthus

- Tree Tobacco – Nicotiana glauca

- California Fuchsia – Epilobium canum

- Mule Fat – Baccharis salicifolia

- Lanceleaf Liveforever – Dudleya lanceolata

- Yerba santa – Eriodictyon californicum

- Blue elderberry – sambucus Mexicana (best guess)

- Wild cucumber – marah macrocarpa

- White sage – Salvia apiana

- Lemonade Berry – Rhus integrifolia

- Miner’s Lettuce – Claytonia perfoliate

- Toyon – Heteromeles arbutifolia

- Sugar Bush – Rhus ovata

- Purple Grass – ?

- Grasses – Several

-

Why I Garden

Everyone has a story about how they got into gardening. For some, it was being introduced to it by a parent or grandparent when they were a child. For others, it was a friends’ passion for houseplants, succulents, or growing the ‘devil’s lettuce’ from a random seed they came across. Whatever the gateway, it is always a great story to hear.

Mine is not a unique one by any stretch of the imagination. Like many, I happened into gardening as a response to depression. Over 18 months, we lost a half dozen loved ones. Death is a natural process of life, but anyone that experiences this kind of loss knows the effect it can have on the psyche. Compounded over time, it begins to add up like interest. I was never in a pit of despair. I felt as though I was functioning just fine. Really, I was running on autopilot and on an empty tank of emotions. In the middle of this period, I found myself sitting and looking at a dirt patch of a suburban backyard and deciding I wanted to change it. The problem was I did not know how to start.

Influences

At this time, I stumbled onto a program from the BBC on Amazon Prime that helped a lot. Big Dreams, Small Spaces was a garden makeover show unlike any I had seen before. The host, Monty Don, was new to me, and his calm demeanor and just “give it a go” mantra inspired me to bring my big dream to my small space. I wish I could say what made his program and message so inspiring. In one of the episodes, he talked about how gardening helped him through a dark period of his life, something that, in retrospect, probably resonated as something I needed to hear. Whatever the case, episode by episode, as I watched, I would go out and apply (more or less) what I had learned or taken. Doing hardscape first. Then figuring out a plant pallet being sure to not overdo it. With the gentle guidance of my spouse, I went from a very geometrical design to something that coaxed you into the space, surrounding you with seasonal wildflowers and perennial shrubbery.

Hard to believe a show from the other side of the planet would have that effect, but Monty Don holds a special place in my heart. I still love watching Gardners World when it’s carried on a U.S. streaming platform.

But there are two sides to every coin. Where I was inspired to do the work came from overseas, I found a passion for California native plants from someone on YouTube.

Read: Embracing the Fifth Season

Joey Santore is a horticulture and botany household name these days with his Crime Pays But Botany Doesn’t website. With a podcast, YouTube, and internet presence, Santore is a raconteur when it comes to talking about plants, plant environments, and why we should care about them. Watching his videos gave me permission to be an inspired novice. Watching and learning from him helped ignite a passion that allowed me to jump headfirst into what felt like a closed-off or snobbish world of native plant lovers. He took no prisoners, and neither would I. I wanted into this world and felt like Santore gave me permission.

With mantras like “Stop Humanity” and “Kill Your Lawn,” this was just the spark of divine anti-creation I needed to kill off what was left of my lawn and ignore the influence of the big box home improvement stores that just wanted to sell me drought-tolerant plants.

I found the inspiration and was given permission. Now all I needed was the know-how.

Learning About Native Plants

With the vision and permission, I needed to learn about plants. Not just any lesson about plants, I needed to consume a lot of information about California native plants and synthesize it into a planting plan for my backyard. Sadly, I did not know where to begin. The internet was not a great help. Yes, it had message boards, websites, and groups, but none of them really captured or conveyed the essence of what it was I needed to know. It was not until my spouse took me to the local native plant nursery that I found the early tools to learn about native plants.

Theodore Payne Foundation in Los Angeles is a bit of a historical anachronism. It was not until recently that planting California native plants came into vogue. With drought becoming an annual recurrence having a bushy green grass yard becomes more expensive. TPF, as the Theodore Payne Foundation is affectionally called, is named after an English horticulturist and gardener that came to southern California in 1893. In time, his passion for native plants led to the creation of several botanic gardens dedicated to the, then, fast disappearing native plant habitats. The foundation after his name, founded in 1960, continues his work. My intersection with TPF began with their nursery but soon led to taking classes, buying books and seeds, and immersing myself in the environment to absorb all the native plant knowledge I could.

Besides trial and error with planting native plants and walking their habitat gardens, the best tool I came away with was the book California Native Plants for the Garden by Carol Bornstein, David Fross, and Bart O’Brien. This one book continues to be a source of inspiration, knowledge, and growth for me on native plant knowledge.

Another great place I found to learn about native plants was the California Native Plant Society. Like any club, CNPS is broken into several local chapters that each serve its unique geographic location and audience. Locally, they host events, plant sales, and host monthly seminars where knowledgeable speakers share their scientific work. It tends to be more on the scientific side of the field, but not so much for a novice to engage with and take something away from it.

Being part of the California Native Plant Society has given me an affection for the work to protect the natural spaces in California. What I found is that I wanted to be more hands-on. This led me to become a certified California Naturalist with the UCANR.

Becoming a Naturalist

I have written a whole post on what it means to become a naturalist. The process, while time intensive, was a hands-on experience that brought everything I had learned full circle. The title, certified naturalist, is a catch-all of sorts to describe an individual who has taken a class with a lab that helps inform their understanding of the natural world as it relates to the state of California. Personally, the naturalist certification synergized these experiences synthesizing a new/better understanding of how they all work in balance.

Today, as a naturalist, I volunteer with a local CNPS chapter to restore native habitat in the Sepulveda Basin Wildlife Reserve, growing and planting regionally appropriate plants to mitigate the encroachment of invasive plants like wild mustards, thistle, and clovers. When able, I like to share with passers-by why we do the work, and the value of removing invasive weeds and planting native species.

One takeaway for me is that, for some, the value of native plants is hard to understand. Often, I hear people say they look like weeds, they look ugly, or they attract bugs. This is what brings me back to California native plants time after time. These plants belong in this environment feeding the native wildlife—something centuries of human presence have degraded. My passion for this vein of horticulture is the growth and cultivation of the natural world and the restoration of local flora and fauna to heal the plant.

It sounds a little hippy-dippy, but after experiencing the loss of so much, I have found a renewed purpose in exploring, understanding, and restoring the natural world. Be it: looking at plants in the wild, collecting a seed, cultivating it into a plant, or putting that plant into the ground—that process of celebrating and preserving the natural world encourages me to continue doing it and sharing it with others.

Today, the grief and depression of losing those loved ones has passed. In its place is a passion for preserving the natural world. What was a barren yard is now a thriving pollinator garden. And what was the burned-out space of the Sepulveda Basin Wildlife Reserve is a budding natural space that will become a thriving ecosystem.

Hopefully, my sharing this about my gardening journey will inspire you to start on yours.

-

Observing the Upper Las Virgenes Canyon Open Space Preserve in May

California Naturalist Outing

Upper Las Virgenes Canyon Open Space Preserve – Victory Trailhead

11:20 a.m.-3 p.m.- Route: From the main (paid) parking lot and starting on the Joe Behar Trail to the left to Fife Drive, looping back to the E. Las Virgenes Canyon Road (fire road) to the start. Round trip, approx. 6 miles.

- Weather: Cool at the start and slightly humid. 64°F, 82°F, and hot under the direct sun at the end.

This was an observation trek to loop on the Joe Behar trail at the Victory Trail Head in the Upper Las Virgenes Canyon Open Space in Woodland Hills, CA.

The parking lot at the start was relatively empty (one car) but with several people returning from the trail. Most were parked in the street in the non-paid area.

Visually, along the hillside, there was a lot of tall dry grass but not a lot of mustard. This surprised me as in recent years, the mustard was tall and thick blanketing the hillside. In past years, the plant would tower well over 6 feet (much like it is in the Sepulveda Basin at the time of this observation). Now, it seemed as though years of removal had paid off as the mustard only remained in patches and along the trail edge. Of the mustard, it was a tall variety with mature purple stalks with sparse leaf clusters. The type and variety, however, escape my ability to discern the variety. Using iNaturalist, my closest approximation is common field mustard (Brassica rapa) which is listed as having been observed in the area previously.

Lots of Reptiles

One thing I observed in abundance was lizards. Most, if not all, seemed to be fence lizards, with many of the smaller/younger ones with yellow-tinted bellies and missing their tails—no doubt the victims of hungry birds or other predators.

My estimation is that for each stride on the trip, there was no fewer than one lizard with many having two or three. This made for a delicate dance at some points to not land my large clumsy foot right where a spooked lizard evacuated to at the sound of my footfalls.

Near the end of the excursion on the return back, I happened upon a snake that was as spooked at my appearance as I was at his, disappearing into the grass and brush faster than I could to get a good look at it. Its presence reminded me of the fresh snake trail I encountered at the Marvin Braude Gateway trail.

Many Oaks, Little Shade

Along the deeply rutted trail, large Valley and Coastal Live oaks dotted the hillsides. Their deep green canopies stretching skyward stood in contrast to the dry tan grasses at the feet. I couldn’t help but wonder if in centuries past their numbers were quadruple what they were now. Scarcely a few on the trail seemed to be more than 50 years old and, of those, several were victims of some pest, storm, or fire and had fallen over dead. Still, some young trees stretched to the heavens and were growing for future generations. Seeing how few trees there were reminded me of something from my naturalist training where, at a point overlooking the San Gabriel Valley, as a group we imagined the world as it may have been centuries past as open plains hosted sage/chaparral and oak forests in thickets. Today, those spaces are filled with people and human-made forests.

Remarkably, in some spots, groves of oaks seemed to cluster in hillside cuts, likely sources of greater ground moisture and microclimates helping to nurse them along. In one spot, maybe 20 trees formed a grove over an acre with a few close to the trail to hint at shade. Most however were far enough from the trail to be a nuisance to get to by the casual climber.

Annuals Everywhere

Along the trail, I took great delight in seeing annuals all along the path. Bird’s-foot Trefoil, Goldenstars, thistle, and the occasional poppy all shared space with black sage, deerweed, and Palmer’s goldenbush. Fiddleneck (though looking tired) and buckwheat entering their showy phase with big pom-poms of flowers. Annuals were not everywhere, but were just enough to make their presence known. There were, of course, sweet clover and cheese wheel weeds in abundance, along with occasional patches of vetch in full bloom with their purple inch-long flowers hanging over like dripping colorful tassels. The Maltese Star-thistle was everywhere but not so high as to make the space look unpassable.

Like the Santa Monica Mountains, the grasshoppers were prolific, always staying a how or two out of each footfall. These grasshoppers (Pallid-winged Grasshopper – Trimerotropis pallidipennis) seemed unremarkable appearance-wise but in great abundance all along the trail. Like the lizards, they occupied every pace of the trip, usually in abundance (five+ in every other pace). It seemed like as the sun came out and that increased, their numbers increased along the trail with me.

Another critter I was surprised to see in such great profusion was European earwigs. With their giant rear pinchers, these detritus eaters were casually sitting atop many of the mustard heads seemingly eating the pollen from the flower. The first I saw doing this surprised me, but within two paces I found plants covered with them doing the same thing. I wonder if the profusion of the European mustard has anything to do with the profusion of European earwigs.

Wet Creeks and Hot Trails

At the middle point of the loop, the trail connects back with the main fire road along a north/south facing route with the full western sun in the afternoon. A wall of black sage, buckwheat, bush sunflower, coyote bush, and deer weed seemed to be thriving in the late spring heat. All of this was flanked by mustard forming, at one point, a trail tunnel that required navigating through. All of the plants looked healthy and robust as I descended the plateau into the lower creek bed.

It was at this point I reconnected to the main fire road and began my trek back to the start. Along this way, I crossed a trickling creek with patches of slow-moving water that formed pools of slow-moving water. Here, tadpoles and small frogs hid in plain sight scattering when a shadow enveloped them. Neither the frogs nor tadpoles were larger than my fingernail. The frogs were grey-mottled and blended into the surrounding soil so well that I scarcely saw them before they would jump away. It was remarkable to see on so warm an afternoon in the open like that.

Closing the loop of the trail, I returned to the start whereupon I stumbled onto two fence lizards playing tag on the visitor sign. All said it was hot, and I was spent. I concluded my outing at the Upper Las Virgenes Canyon Open Space in the West San Fernando Valley.

Field Observations

- Many hikers at start.

- Several at end, some jogging.

- Mountain bikes, silent and at speed on the trail.

- Lots of grasshoppers, lizards, earwigs, ladybugs, and hover flies.

- Decent trails, some ruts, no washouts.

- Running water in creek in lowest points.

- Dragon flies (Orange and blue).

Observed Species

- California Sage – Artemisia californica

- Valley Oak – Quercus lobata

- Coast Live Oaks – Quercus agrifolia

- Black sage – Salvia mellifera

- Mustard (field mustard?) –

- Common wild Oat(?) – Avena fatua

- American Bird’s-foot Trefoil – Acmispon americanus

- Goldenstar – Bloomeria crocea

- Common Fiddleneck – Amsinckia intermedia

- Buckwheat – Eriogonum fasciculatum

- Woollypod Milkweed – Asclepias eriocarpa

- Milk Thistle – Silybum marianum

- Maltese Star Thistle – Centaurea melitensis

- Annual yellow sweetclover – melilotus indicus

- Laurel Sumac – Malosma laurina

- Cheeseweed Mallow – Malva parviflora

- Deerweed – Acmispon glaber

- Purple Clarkia – Clarkia purpurea

- Hairy Vetch – Vicia villosa

- Telegraph weed -Heterotheca grandiflora

- Southern Bush Monkeyflower – Diplacus longiflorus

- Hyssop loosetrife – Lythrum hyssopifolia

- Chaparral Mallow – Malacothamnus fasciculatus

- Palmer’s Goldenbush – Ericameria palmeri

- Grasses – Several

- Pallid-winged Grasshopper – Trimerotropis pallidipennis

- European Earwig Complex Forficula auricularia

- Acmon Blue – Icaricia acmon

- Western Fence Lizard – Sceloporus occidentalis

- Flame skimmer dragonfly (Orange) – Libellula saturate(?)

- Hover flies

- Lady Bugs

- Tadpole

- Frogs

Planting Natives