Let me preface this by saying I believe we all have an inner naturalist. That part of us that’s drawn to organic vegetables, clean water, or a cool breeze through dappled sunlight filtered through tree leaves—the list could go on and on.

The UC Naturalist program says:

“the UC California Naturalist Program is designed to introduce Californians to the wonders of our unique ecology, engage the public in study and stewardship of California’s natural communities, and increase community and ecosystem resilience.”

To get there, one needs to find, or tap into, that inner passion for the natural world.

But nature is complicated and knowing where to begin or how to put all the different pieces together can be a challenge. When does being interested in nature become a passion for studying the natural world? More specifically, when does it become a passion for studying the natural world around you?

I don’t have an easy textbook answer for you. What I can describe is my journey to become a California Naturalist and what aspects inspire me to want to discover more.

An Urban Naturalist

The concept of a naturalist seems straightforward, someone who studies nature. How does one apply that in the urban setting? The notion of studying nature in a highly developed city like Los Angeles seems like an impossible thing to do with grids of suburban homes, miles, and miles of paved roadway. Not to forget the patchwork of small to intense industrial and commercial development that has come to define the metropolis. All of this, however, occupies what was once open space grass meadows, creek and riparian floodplain, oak, and sage/chaparral scrub forests.

Somewhere amidst the urban and suburban forest is the climates memory of the natural and native space. It’s this memory that has allowed a host of unique plants to not only grow here but thrive, in times past, and desperately struggle as the long-term impacts of mankind’s footprint transform the world around it.

Important to note, California is home to more endemic (unique, only occurring here) species than any other state. The California Department of Fish and Wildlife says that California hosts:

“6,500 species, subspecies, and varieties of plants that occur naturally in the state, and many of these are found nowhere else in the world.”

It’s also home to close to 30,000 species of bugs, fish, animals, birds, and amphibians. (Greg de Nevers, 2013)

Within that framework, humans have occupied the region in some capacity for more than 4,000 years going back to the early hunter gathers that evolved to become the Gabrielino-Tongva. Some sources put the first arrivals as far as 10,000 years ago, while others speculate at more than 100,000 years ago. Since that arrival, waves of occupation have washed across the state causing wave after wave of development and change to the landscape.

Anthropogenic Effects

As humans have occupied the natural space of California, each group cultivated the landscape to meet their needs.

Ancient peoples’ cultivated oaks, chia, and wildlife for substance and prosperity. Those who came after introduced grasses and ranchos for cattle, farms to grow crops and dairy, and orchards of citrus that grew well in the Mediterranean climate. All along, the occupants sought to shape the natural landscape to their will to get out of it some product for sustenance, profit, or pleasure.

Read: Best Hiking Shoes for Wide Feet with Plantar Fasciitis

In those pursuits, the city of Los Angeles has erupted as if out of the soil to meet the needs of modern occupants, disrupting what were once natural ecosystems and creating a fragmented patchwork of industrial, suburban, paved over spaced in-between groomed grassy spaces and remnant wild open space. This mix of developed and undeveloped patchwork has created a unique kaleidoscope of native plants co-habituating with non-natives fighting an increasingly losing battle over territory.

Wild vs. Semi-Wild

What does this battle have to do with being a naturalist? In many ways, I see this conflict between invasive/native plants as the epitome of our occupation in the Southern California region. Never mind the urban forest of lawns, water-hungry trees and shrubs, and agriculture. Our unique climate has given rise to a unique number of species. In the anthropogenic pursuits of freeways, skyscrapers, and suburban sprawl, we’re also coming to realize the cost of our development as heat (from climate change), health (from healthcare disparity and wealth inequality), and our ability to own or steward the remaining open space to preserve what little of the past is still present. Much of what we would consider as wild space is really space still within cellphone service and walking distance to a convenience store.

Very little is “wild” in the sense of what our grandparents would think of it as. I doubt our own grandchildren would be able to imagine the little we have now.

This is part of the seed that grows into becoming a California Naturalist.

In my own process, my study has taken me through several “wild” and “semi-wild” spaces. What I was able to see and take mental stock of was how nature, literally, finds a way. In much of the two sites of study, there has been a tremendous volume of human intervention: one in space necessary for human passage and the other on the outskirts of suburbia. In both places, it was impossible to not see the impacts of current and past anthropogenic influences.

What did stand out, in contrast, was how one location (the Lower Arroyo) had several human interventions to bring back native plants in places long devoid of their presence because of the haphazard introduction of non-natives, human development, or liminal gaps between two ecosystems, split by the megalithic architecture of soaring freeway overpasses.

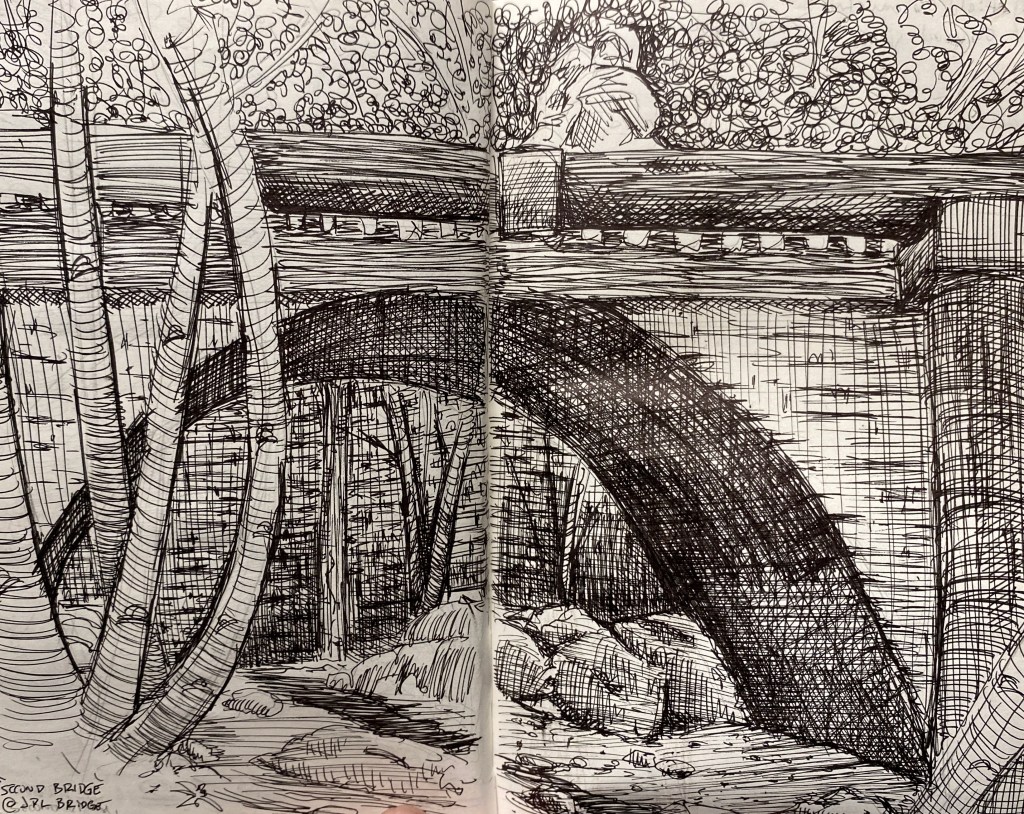

In the second location (the Upper Arroyo) The human presence was less pronounced, but still noticeable with old bridges, cabin foundations, and creature comforts marking the locations of long-vanished habitations. Roads, soaring utility poles, and a twisting maze of piping from waterworks announced that humans were still very much present in the space.

In both examples, the wild vs. semi-wild felt less important to the fact that they were both just a stone’s throw from the rest of civilization. They existed in a mostly natural state because the environment dictated that they must. That the plants that grew in these regions, should and did grow there. What dictated how and where they grew was less about how it was planted and tended (if at all) and more about the underlying ability of the space to sustain the plants’ existence.

Patchwork Fragmentation

One of the last lessons in this process of becoming a California Naturalist was a lesson on community fragmentation. More specifically, the drivers of diversity might very much have to do with landscape ecology.

In short, the concept is that certain plants grow in communities of other plants in an ecosystem of support relative to the environmental aspects around them. In particular: how much groundwater (moisture) there is, the slope of the space and the quantity of and type of sun it gets, and the presence of plants that can act as incubators for other plant species to get established and grow in the space. The text for this course describes this landscape ecology as a mix of patch, matrix, mosaic, and corridor landscapes working in unison but fluid over time.

In the field, where this patch landscape ecology took shape was in observing how vegetation (in both wild and semi-wild spaces) followed a similar pattern of growing where the environment was best suited to nurture and encourage its growth.

In gardening terms, the right plant in the right place.

It struck me that this patchwork ecology that was occurring in the wild spaces was similar (if not the same thing) happening in the urban spaces as native and non-native plants become opportunists and populate hospitable landscapes, if not inviting, to exist in.

In effect, the anthropogenic impacts of human occupations are themselves, creating new ecosystems into which native plants can find footholds. It was in this context that the picture of my becoming a California naturalist crystalized.

Accidental Ecosystems

The effects of all this city building have been the construction of a patchwork landscape of micro-climates, islands of ecology, and an urban forest of chemically fertilized lawns dotted in a patchwork quilt of weedy native lots, small native gardens, and hillsides aggressively holding to their fire-prone sage/chaparral ecosystems. At the same time, what was once wide riparian flood plains, oak forests, and meadowlands have been subsumed into the new urban sprawl.

It’s out of this new landscape, these natural and reclaimed spaces, that being a naturalist in the urban world exists. We think of suburbia as being all lawn and bungalow homes, when, the unique ecosystems of the pre-human California still exist in the patchwork landscapes between the anthropogenic footprints of human occupation. It may be as simple as a ground out millstone pits in rocks from early human occupants or large concrete water channels redirecting the flow of water through a space.

The Suburban Naturalist

The journey of becoming a California naturalist was less about a hard depth of subject plunge into the aspects of animal species, plant taxonomy, or geography (though these are all aspects of the process). Rather it seems more akin to understanding what’s going on in the spaces around you and how those things exist: place to place, season to season, location to location, even in a suburban setting.

The environment is a dynamic and fluid space. Ecosystems exist in many aspects and in many configurations with a variety of inputs and pressures. While human inputs create a unique set of pressures on a landscape, so do they create new habitats and ecosystems. From that understanding that an appreciation for studying nature can take hold.

17 responses to “Becoming A California Naturalist”

[…] Read: Becoming A Naturalist […]

LikeLike

[…] Read: Becoming A Naturalist […]

LikeLike

[…] Read: Becoming A Naturalist […]

LikeLike

[…] Read: Becoming A Naturalist […]

LikeLike

[…] Read: Becoming A Naturalist […]

LikeLike

[…] Read: Becoming A Naturalist […]

LikeLike

[…] Read: Becoming A Naturalist […]

LikeLike

[…] Read: Becoming A Naturalist […]

LikeLike

[…] Read: Becoming A Naturalist […]

LikeLike

[…] Read: Becoming A Naturalist […]

LikeLike

[…] Read: Becoming A Naturalist […]

LikeLike

[…] Read: Becoming A Naturalist […]

LikeLike

[…] Read: Becoming A Naturalist […]

LikeLike

[…] Read: Becoming A Naturalist […]

LikeLike

[…] have written a whole post on what it means to become a naturalist. The process, while time intensive, was a hands-on experience that brought everything I had learned […]

LikeLike

[…] Read: Becoming A California Naturalist […]

LikeLike

[…] Read: Becoming A California Naturalist […]

LikeLike