California Naturalist Outing

Upper Arroyo Park/Trail

JPL Bridge – Millard Canyon

8:45 a.m. – 11:30 A.m.

- Route: Entering the canyon at the fence line, up the old road to the oak forest at the El Prieto Canyon Trail.

- Weather: 71°F (high of 89°F at end). Sunny and clear, not a cloud in sight.

Visit to the Lower Arroyo Seco

For this trip into the space, our goal was to look at the oak forest up into the El Prieto Trail. This path snaked up the northern side of a steep sloped canyon creating a unique example of patch ecology between riparian creek below, oak forest along the trail line and sage/chaparral high up on the hotter sun exposed slopes. This mix of space created an interesting microclimate or sorts from the presence of water, shade producing tree structures (oaks) the hot dry slopes that took the brunt of the morning and daytime sun.

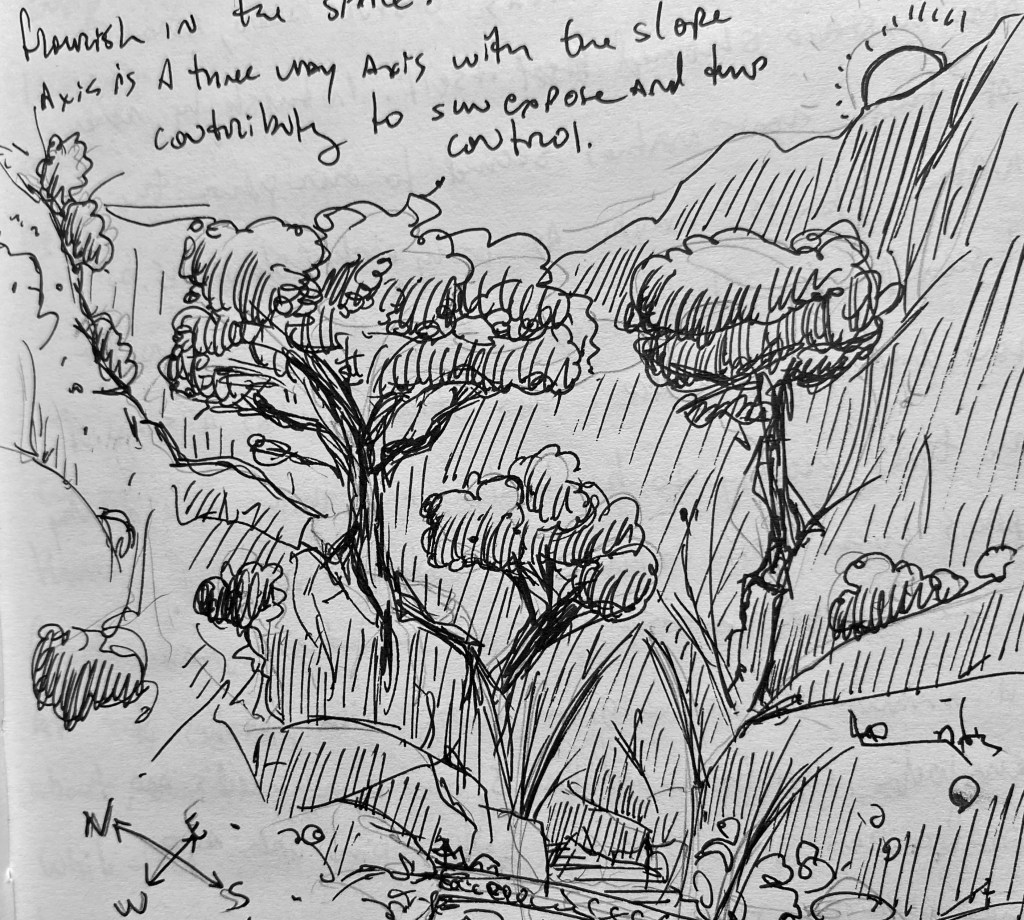

In this configuration, the two axes of water and temperature made for the perfect boundary zones such that each of the patch communities could thrive and flourish in the space. I would add that the axis is a three-way measurement with the slope contributing to the sun exposure and temperature control.

In much of the mixed communities, the leaf litter combined to make a thick mulch layer—three to four inches deep. Below the detritus, the loamy soil was still damp to the touch, despite having rained a week or more prior. And, like any good opportunists, non-native plants such as castor bean, Asian elm and invasive mustard showed itself in the space. Interestingly, none of these non-natives seemed to overpower the native plants—maybe as only early colonizers, but it seemed they had a much harder time growing in the non-disturbed space. This struck me as a sign of the trail ecology as being healthy and thick while nearby spaces with less water and more exposure, struggled. Trees and shade played a huge factor. In the dappled sunlight on the edges, grasses of all manner of origin grew along with patches of hemlock, coastal wood ferns, scorpion weed, and pacific pea grew side by side poison oak and other riparian ecology.

Throughout, lots of Chillicothe grew through and into shrubs and trees along the trail, along with large healthy toyon and black sage. All of which in its own unique biologic niche occupying and sharing spaces that to a casual passerby would seem impossible to call home. In many cases, to get a plant ID or even a snapshot would require a daring feat of leaning over an edge of the steep slope to grab a branch or flowering stem.

For early April, the space felt alive and happy.

Even the wildlife was out in abundance. Hover flies and gnats darted around, a beehive of some composition hummed just off the trail, and hummingbirds, wren, doves, and woodpeckers foraged and went about their daily existence. I was surprised at the number of butterflies and caterpillars about, even so much as to capture a photo of a White-lined Sphinx caterpillar just going about its business.

As unique sightings go, I observed a few interesting mushrooms, some beetles, and birds, just walking through the space. On one long fallen dried log in an open dry space, remnants of what looked to be Turkey Tail like fungus, long dried and sun bleached, clutched onto the length of tree.

At one location, I used the BirdNET app to ID a Bewick’s wren and a Nuttall woodpecker—both doing their bird thing not too far off the narrow path. Many of the birds that chose to not be seen and stayed at considerable distance from any passersby.

On my way back, I stepped down into an open glade to see how a riparian niche over topped by oaks and tall alder and willow. The floor of which was covered, in some places nearly a feet deep, with fallen leaves and detritus. This space had a magical feel as highly filtered sunlight barely made it through the canopy making the whole space look like a post-card. That magic, however, was disturbed by signs of man’s presence from an abandoned tire and basketball, both slowly being swallowed by the falling organic matter.

These human intrusions to the otherwise natural space were just one example of our presence. On the trail, there were several hikers, people on mountain bikes, and objects lost by both. Of the people on bicycles, many occupied the trail going great speeds which seemed to present a significant hazard to both human and fauna. Personally, I had to dodge several with their fast-approaching sheep bells announcing their presence before coming into sight. I suppose this is just a hazard of the trail and something to watch out for like a horseback rider, bear or, rattle snake.

Lastly, I used this excursion to gather some data as it relates to the different plant communities and in one unique plant patch that encompassed riparian, sage, chaparral, and oak forest which yielded interesting results. In just a short space, plant diversity seemed to explode in a mix of variety and location.

After these surveys I returned to my starting point, checked myself back in and departed for the day.

Field Observations

- Many mountain bikes (in the time of my observations)

- 4 trail hikers

- Bird calls from Berwick’s Wren and a Nutall woodpecker

- Several mushrooms (2 fresh, one set dried)

- Large trash/debris (tire/basketball in creek)

- Poison oak in nearly every cooler/wet space.

- Lots of insect life (diabolical ironclad beetle, gnats, bees, butterflies

- White-lined sphinx caterpillar

- Many lizards along trails

- Old concrete gabion channel walls (creek flow chokes)

- More exotic plants (acacia and Pacific pea)

- Hemlock in great abundance

- Patch habitat following sunlight/slope paths

- Grasses growing in niche biomes

- Thick detritus leaf mulch

Observed Species

- Alder – Alnus rhombifolia

- Arroyo Willow – Salix lasiolepis

- Ash – Fraxinus genus (non-native)

- Black Sage – Salvia mellifera

- Black Walnut – Juglans californica

- Buckwheat – Eriogonum fasciculatum

- California Sage – Artemisia californica

- caterpillar scorpionweed – Phacelia cicutaria

- Chilicothe – Marah macrocarpa

- Coastal woodfern – Dryopteris arguta

- Common Conecap – Pholiotina rugosa

- Cootmundra wattle – Acacia baileyana

- Desert wishbone-bush – Marabilis laevis

- Diabolical Ironclad Beetle – Phloeodes diabolicus

- Dodder – Cuscuta californica

- Elderberry – Sambucus melanocarpa

- Elm (Chinese elm?)

- Grasses (many)

- Grasses (various)

- Hemlock – Conium maculatum

- Invasive/non native mustards

- Laurel Sumac – Malosma laurina

- Miners lettuce

- Mulch Maids – Leratiomyces percevalii

- Mule Fat – Baccharis salicifolia

- oak(s)

- Pacific pea – Lathyrus vestitus

- Poison Oak – Toxicodendron diversilobum

- streambank Springbeauty – Claytonia parviflora

- Sunflower

- Toyon – Heteromeles arbutifolia

- Weeds (many)

- Western Sycamore – Platanus racemosa

- White-Lined Sphinx – Hyles lineata

4 responses to “Upper Arroyo Seco – Visit 4”

[…] 2 | Visit 3 | Visit 4 | Visit […]

LikeLike

[…] 1 | Visit 3 | Visit 4 | Visit […]

LikeLike

[…] 1 | Visit 2 | Visit 4 | Visit […]

LikeLike

[…] Visit 1 | Visit 2 | Visit 3 | Visit 4 […]

LikeLike